Understanding exact sequences

Let’s start with a motivating question I had from group theory: if $N \trianglelefteq G$ is a normal subgroup, is it necessarily true that $G\cong G/N\times N$? Looking at non-abelian groups quickly shows that the answer is no (take the dihedral group $D_3=\langle r,t \mid r^3=t^2=1, rt=tr^{-1}\rangle$ and the normal subgroup $\langle r\rangle\cong \mathbb{Z}/3$).

I later learned about semidirect products $\rtimes_\phi$, which generalize the direct product $\times$. But even this was insufficient to describe group decompositions.

Eventually, I was turned to a diagram that looked something like this

$$ \begin{equation} 1 \xrightarrow{} N \xrightarrow{\iota} G \xrightarrow{\pi} Q \xrightarrow{} 1, \end{equation} $$

and was told that it was a short exact sequence if $\iota$ is injective, $\pi$ is surjective, and $\ker{\pi}=\mathrm{im}~\iota$. This was supposed to reveal some structure to the group. I want to look deeper into that here, and see where exact sequences have shown up elsewhere.

Unpacking the definition with quotient groups

Let’s start with the familiar example: the objects in (1) are groups and the arrows are group homomorphisms. In particular, we will look at when $Q$ is the quotient

$$ \begin{equation} 1 \xrightarrow{} N \xrightarrow{\iota} G \xrightarrow{\pi} G/N \xrightarrow{} 1, \end{equation} $$

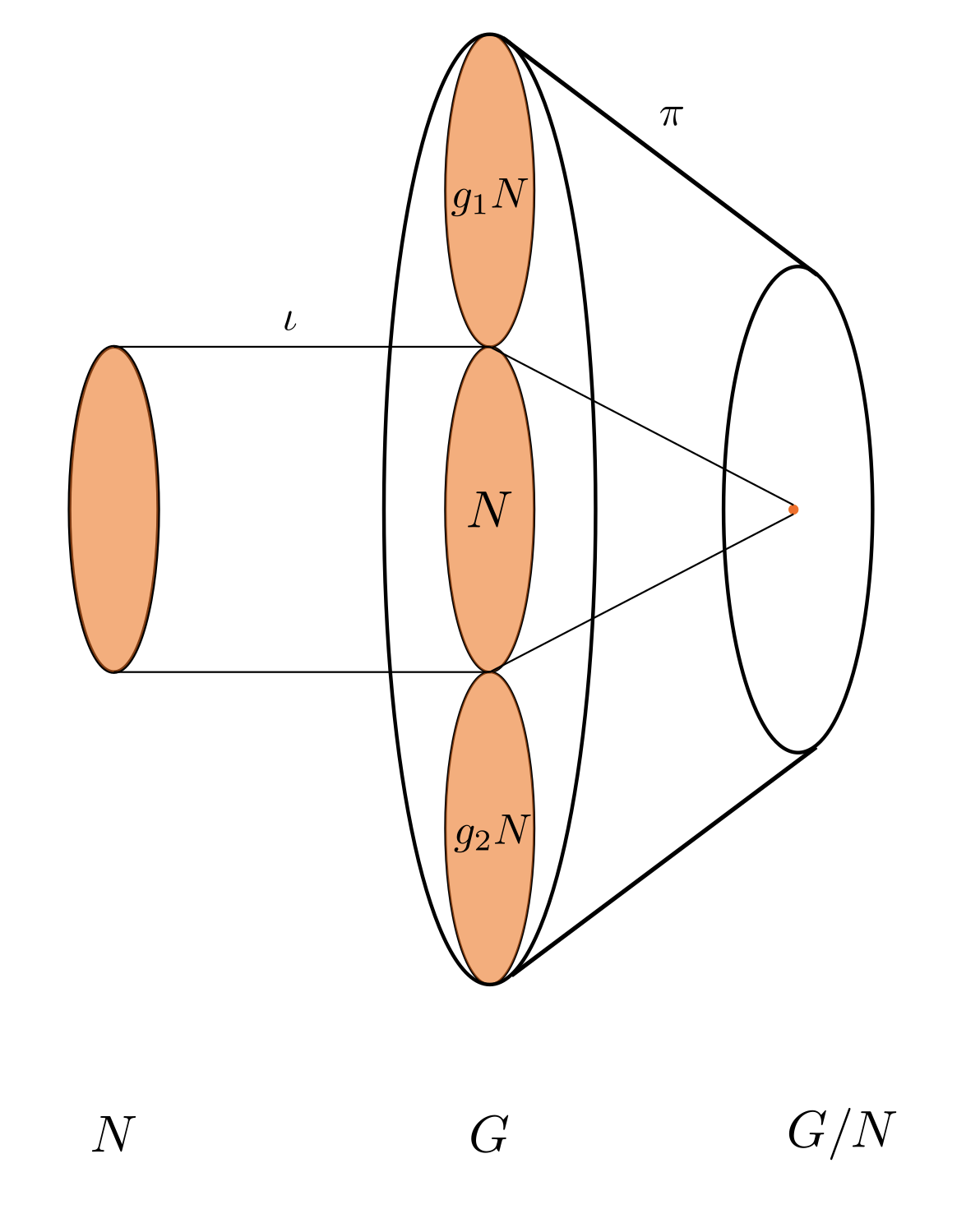

It makes sense to think of $\iota\colon N\to G$ as an inclusion map (indeed, $N$ is just a subset of $G$, so the inclusion map is given by $n\mapsto n$) and $\pi \colon G\to G/N$ as a natural projection (i.e. $g\mapsto gN$).

Let’s look deeper into what the statement “$\mathop{\rm im}{\iota}=\ker{\pi}$” means. $\iota$, as an inclusion map, effectively embeds $N$ into $G$ (that is, it places the algebraic structure of $N$ into $G$). By saying that $\ker{\pi}$ is the image of $\iota$, we are saying that $\pi$ sends everything in the image to the identity. Why is this intuitive? Recall we define the quotient group $G/N$ as the cosets of $N$. Specifically, the identity element is just $N$. This means that we represent $N$ as a single element in $G/N$.

An exact sequence of groups. $g_1N$, $g_2N$ are cosets of $N$ inside $G$.

In general, a short exact sequence tells us that the object $N$ embedded in $G$ will be identified with a single element in $Q$.

(Long) exact sequences and complexes

Now we can start to look at larger sequences of objects, such as the following:

$$ \begin{equation} G_0 \xrightarrow{\phi_1} G_1 \xrightarrow{\phi_2}\cdots \xrightarrow{\phi_{n-1}} G_{n-1}\xrightarrow{\phi_n} G_n. \end{equation} $$

This sequence is exact if $\mathop{\rm im}{\phi_i}=\ker{\phi_{i+1}}$ for $1\leq i\leq n-1$. Perhaps a nicer way to relate this to the previous discussion is the equivalent definition.

Definition.

A sequence

$$ \begin{equation*} G_0 \xrightarrow{\phi_1} G_1 \xrightarrow{\phi_2}\cdots \xrightarrow{\phi_{n-1}} G_{n-1}\xrightarrow{\phi_n} G_n. \tag{3} \end{equation*} $$

is exact if the sequences

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} 1 \xrightarrow{} K_1 \xrightarrow{\iota} &G_1 \xrightarrow{\phi_2} K_2 \xrightarrow{} 1 \\ 1 \xrightarrow{} K_2 \xrightarrow{\iota} &G_2 \xrightarrow{\phi_3} K_3 \xrightarrow{} 1 \\ &\vdots\\ 1 \xrightarrow{} K_{n-1} \xrightarrow{\iota} &G_{n-1} \xrightarrow{\phi_n} K_n \xrightarrow{} 1, \end{split} \end{equation} $$

where $K_i = \mathop{\rm im}{\phi_i}$, are all short exact.

Example (The long sequence of forms).

Let $M$ be a smooth, $n$-dimensional manifold (if you don’t know what a manifold is, it’s good enough to consider $M=\mathbb{R}^n$. Despite this, as with everything in differential geometry, the notation in this example is hard to unpack without knowing about manifolds). Let $\Omega^k(M)$ be the $\mathbb{R}$-vector space of all $k$-forms, that is,

$$ \Omega^k(M) \coloneqq \left\{\omega\colon M\to {\bigwedge}^k(T^*M)\colon p\mapsto \omega_p \right\}, $$

i.e. $\omega_p\colon \underbrace{T_pM\times \cdots \times T_pM}_{k\text{ times}}\to \mathbb{R}$ is an alternating, bilinear map in the tangent space of $M$ in $k$ entries. Letting ${\rm d}\colon \Omega^k(M)\to \Omega^{k+1}(M)$ be the exterior derivative, we have a sequence (not necessarily exact!)

$$ \begin{equation} \Omega^0(M) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \Omega^1(M) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \Omega^2(M) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \cdots \end{equation} $$

Why even bother talking about this if the sequence is not necessarily exact? We say that a sequence (e.g (3)) is a (chain) complex if it satisfies the weaker condition that $\mathop{\rm im}{\phi_i}\subseteq\ker{\phi_{i+1}}$. I think of this as “nothing lasts very long in a complex;” any nonzero term will become zero after it passes through two arrows.

We can prove that $\rm d\circ d\colon \Omega^k(M)\to \Omega^{k+2}(M)$ is the trivial map, making (5) a complex (in particular, the de Rham complex). This leads us to ask: for what manifolds $M$ is de Rham complex exact? An important example is $M=\mathbb{R}^3$, with de Rham complex

$$ \begin{equation} \Omega^0(\mathbb{R}^3) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \Omega^1(\mathbb{R}^3) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \Omega^2(\mathbb{R}^3) \xrightarrow{\rm d} \Omega^3(\mathbb{R}^3) \end{equation} $$

I don’t want to cover its importance here, but there are natural connections between the spaces of $k$-forms and scalar functions/vector fields. One result is that in $\mathbb{R}^3$, a vector field $\mathbf{F}$ is the gradient of some function $f\in C^\infty(\mathbb{R}^3)$ if and only if $\mathop{\rm curl}{\mathbf{F}}=0$.

Next up: homology and cohomology

By requiring $\mathop{\rm im}{\phi_i}\subseteq\ker{\phi_{i+1}}$ for a sequence to be a complex, we see that any exact sequence is a complex. There’s a large gap between complexes and exact sequences. This would be a nice motivation to start looking at homology and cohomology: how far apart a complex is from being exact.