Graph ends and their purpose in geometric group theory

I’ll give an intuition for how mathematicians define what graph ends are, and explain their use in geometric group theory. However, before I can do that, I’ll explain what ends are in a graph theory perspective.

What are ends?

The word ends is a little confusing, because they don’t really represent the “end” of a graph, at least not how we would define an end in real life. Think of a rope. If two teams were playing tug of war on that rope, we know that it has two ends that the opposite teams would tug on. Now if this rope is of finite length (it probably is), then we would typically call the two points at the end of the rope the ends (obviously).

However, knowing these “ends” isn’t that useful when talking about graphs that are infinite (which coincidentally are a lot of the interesting ones).

So how would we define the ends of a graph that is infinite? Well the simplest thing to check is a straight, infinite line. We know it has two ends: to the left and to the right.

Figure 1: An infinite line

What can we say about these ends? Well as we get further from the center of the line, they always get further from each other. What else? Well lets look at another graph.

Figure 2: A binary tree

I’m sure that you’ve come across a binary tree in your life, whether you realized it or not. The basic idea is that we start from the top, and we have two options of how to continue down. Then we have two more options from them, and the tree continues (I’m assuming this tree is infinite).

What do we call an end on this? Well there are plenty of paths that go to infinity, (in fact, $2^{\aleph_0}$ many) and they all certainly are distinct.

Maybe a good starting idea is to cut the top vertex and the edges its attached to. Then we end up with two completely separated (disconnected), but infinite graphs. Can we conclude that there are only two ends? No! because that definitely contradicts what our intuition tells us about this graph.

So let’s cut the next two vertices on the way down. Now we have four infinite graphs that are completely separated. As we continue, the number of separated graphs just gets bigger and bigger.

Compare this to the number line, which, no matter how many edges we remove to “separate” the infinite ends, there always are two infinite ends (try to come up with some other way, it’s impossible).

To formalize this, I need to introduce some more mathematical ideas about graphs.

The formal definition of a graph $\Gamma$ is a set a vertices $V(\Gamma)$, and edges $E(\Gamma)$ that connect the way you expect them to, edges connect vertices together. Additionally, the graph must be connected, meaning that there aren’t any vertices we can’t reach from any other vertex.

Definition (Ball). The ball of size $D$ around a point $x_0 \in \Gamma$ consists of all edges that are a distance of $D$ or less away from $x_0$. We denote this set $B(x_0, D)$.

Now for a graph $\Gamma$, I want you to cut all edges in said ball around of size $D$ around the point $x_0$. The formal way to write this would be $\Gamma \setminus B(x_0,D)$. Now look at the number of infinite graphs that you just created by making this cut. As we make our cuts bigger and bigger, that number ends up becoming the number of ends on the graph!

Sometimes, as I will show later, we can’t ever make a “cut” (of finite size) that is good enough to separate the graph into definite sets, but when we can, we call this an finite essential cutset.

0 Ends: Any finite graph

It should be clear now that any finite graph has $0$ ends, because we definitely don’t have a way to take a finite graph and cut it into infinitely many graphs. Conversely, there definitely isn’t a way to split an infinite graph into a bunch of finite disconnected graphs with a finite number of cuts. So a graph has $0$ ends if and only if it is finite.

2 Ends: The large (infinite) rope

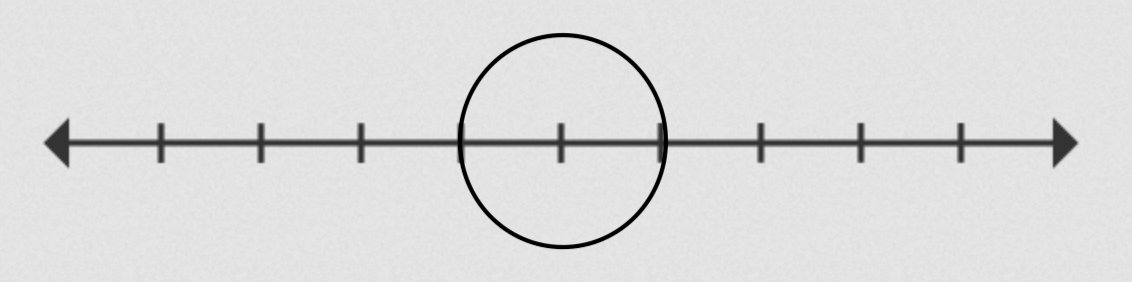

Let’s make a cut on the rope:

Figure 3: A rope cut

If we remove all the edges on that ball, then we end up with two infinite sets that aren’t connected to each other. It makes sense as we increase the radius of the ball, centered at the same point, we would still have two disconnected, infinite sets. Therefore, the infinite rope has two ends.

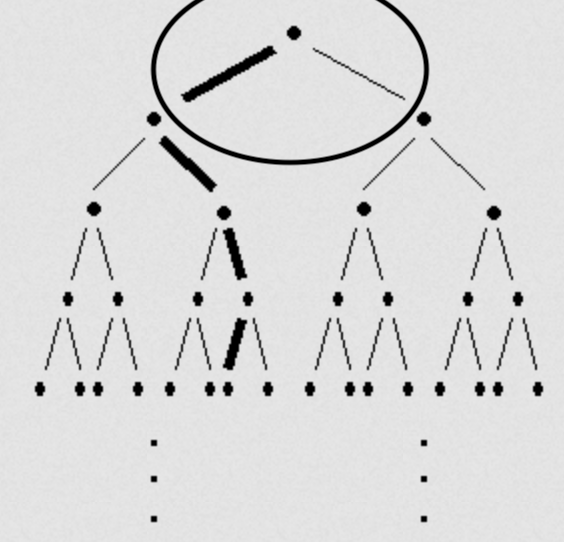

Infinite Ends: The binary tree

Figure 4: A binary tree cut

Removing every edge in the first ball gives us two disconnected, infinite sets, so there are two ends right? Well if we increase the size of the ball, the number of disconnected, infinite sets just keeps getting bigger, and it never really stops growing. In fact, the root of any disconnected set that hasn’t been cut off will result in two, newly created sets after it does get cut. Therefore, the (infinite) binary tree has infinite ends.

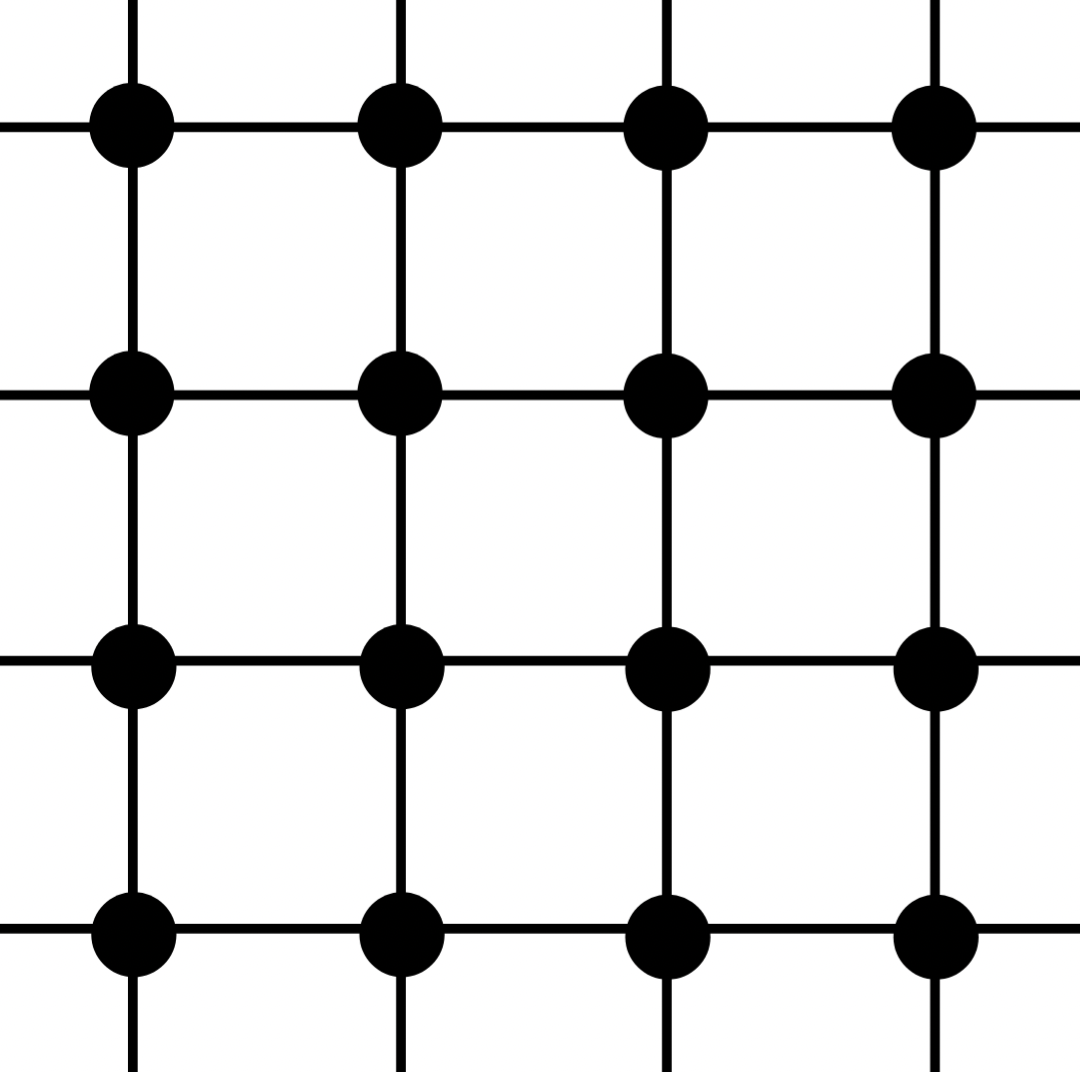

One end: The coordinate lattice

This one should build the idea the most in your head, but it may not seem intuitive: the lattice graph has only one end.

Figure 5: The lattice graph

What? you say, but the lattice is a bunch of ropes attached to each other, why would they not have infinitely many ends? Well notice that as we increase the size of our ball, we can always create a path around the ball from every vertex outside the ball to each other, meaning that they are all connected. So really all the “ends” of this graph are connected to each other, and we only have one end.

One additional note to help ease any concerns:

Proposition. The point that we choose to center the ball cut ($x_0$) does not matter; as we approach infinity, the same number of ends will reveal themselves.

Applications to Geometric Group Theory

Groups can be represented geometrically by Cayley Graphs, which take the generators of the group as directed edges, and the elements of the group as vertices.

Proposition. The number of ends in the Cayley graphs of two groups does not change if the groups are quasi-isometric.

Quasi-isometry is one of the most important principles in geometric group theory, so having this invariant is very useful. Note: this doesn’t mean that two groups are quasi-isometric if they have the same amount of edges (a.k.a. the converse is not true), but it does mean that we can rule out two groups being quasi-isometric if they do not have the same number of edges on their Cayley graph. Additionally, the problem of counting ends simplifies a lot for group Cayley graphs:

Proposition. A Cayley grpah has either $0, 1, 2,$ or $\infty$ ends.

I won’t give a concrete proof here, but note that if a graph has $3$ ends (the same applies for any other finite value $\geq 3$), then we can show that we can move the ball that separates the group into multiple ends into infinitely many places (through the fact that a group can act on its own Cayley graph). This means that when we can show that the number of ends are greater than $2$, we know that the graph has infinitely many ends.

Finally, to finish off, there is something useful we can get for one of the end values:

Theorem. If $\Gamma = \mathbf{Cay}_{A}(G)$, the Cayley graph for a group $G$ with generators $A$, and $\lvert \mathrm{Ends}(\Gamma) \rvert = 2$, then $G$ has a finite index subgroup isomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}$.

Obviously this is true for $\mathbf{Cay}(\mathbb{Z})$ (which has two ends), because the group is $\mathbb{Z}$. However, the power in this theorem that if there are two ends to a Cayley graph, then we automatically know a property of a finite index subgroup, and gain more information about the structure of the larger group.