Can a machine learn mathematical structure?

When I think of machine learning, I tend to think about estimation; a machine learning algorithm is a method of estimating a function given a (usually large) set of data. As a result, I’ve primarily seen machine learning used when the function we are trying to estimate is assumed to be continuous (or differentiable, smooth, etc.), because then you can use nice results from analysis to prove convergence. But algebraic structures like groups can be discrete objects, where there is no way to smoothly interpolate between two group elements. Moreover, groups adhere to very strict rules that dictate how they can be studied, which makes this continuous way of thinking hard to apply – I mean, it’s hard to imagine that a machine learning model, just armed with data about groups, functions between them, and some backpropagation, could reach the isomorphism theorems. Despite this, the research I did last semester opened my mind more to using classical machine learning methods to get structure of discrete groups, given that we ask train the machine on the right questions.

I would like to thank our faculty advisor, Professor Jordan Ellenberg, our graduate student advisor, Karan Srivastava, and my fellow undergraduates Sophia Cohen, Donald Conway, Noah Jillson, Jimmy Vineyard, and Alex Yun, for their hard work on this project.

All of our code for this project is available on GitHub.

Background on modular forms and our problem

A popular topic in mathematics is the study of modular forms (especially in the 1900s, culminating with the proof of Fermat’s last theorem).1 The basic idea with modular forms is to let the group $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ (the set of $2\times 2$ matrices with integer entries and determinant $1$), otherwise known as the modular group, interact with the upper-half plane $\mathbb{H}$ of the complex numbers by the equation

$$ \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} \cdot z \coloneqq \frac{az+b}{cz+d}, $$

and study how it changes the upper-half plane. It can be shown that this is a group action on $\mathbb{H}$, so it has a quotient $\mathbb{H}/\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ (i.e. identifying two points if there is a matrix that can get us between them using the action above) that is very interesting. Most applications of this action rely on studying “nice” complex-valued functions that are unchanged (up to some fudging factor) by the group action.2 We call these modular forms.

Another question we may ask is what happens if we look at modular forms that are unchanged under the action of some subgroup $H \leq \mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$? For instance, Jacobi proved in 1834 an exact formula for the number of $4$-tuples of integers $(a,b,c,d)$ that satisfy $a^2+b^2+c^2+d^2=k$ for each integer $k$. A common proof uses modular forms, where the group $H$ is

$$ \Gamma_0(4) \coloneqq \left\{ \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} \in \mathrm{SL}_2(\Z) \mid \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} \equiv \begin{bmatrix} * & * \\ 0 & * \end{bmatrix} \pmod{4} \right\}, $$

i.e. matrices in $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ whose entries reduced $\bmod{\:4}$ have a zero in the bottom-left.

Finite-index subgroups of the modular group

So subgroups of the modular group are useful. Can we classify all of them? Since $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ is infinite, it would be a lot of work. In the context of modular forms, the finite subgroups are of little importance. In fact, some infinite subgroups are not useful. For a subgroup to be “useful,” we want the size of it to be not too much smaller than the size of $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$. But then both of the groups would infinite! However, with some careful definitions in group theory, we can define what it means for some subgroup to contain some fraction of the elements of $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$.

Definition (Subgroup index). If $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ contains $n$ copies of $H$ inside it, then we say that $H$ is index $n$ in $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$.

It is particularly important to us to find the finite index subgroups of $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$. One example is the $\Gamma_0(N)$ group defined above (where we replace $4$ with $N$ for any natural number). Another example (and the main star of the show) is the Sanov subgroup

$$ \left\langle \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\right\rangle, $$

which is the group of all matrices that are products of $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$, $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$, and their inverses.

Our goal was to make a computer learn how to determine if a subgroup of the modular group, or more generally $\mathrm{SL}_n(\Z)$ for $n\geq 3$, had finite or infinite index. This problem does not have an easy solution in general, and some questions are still unanswered for $n=3$.3

Reframing the problem for a computer

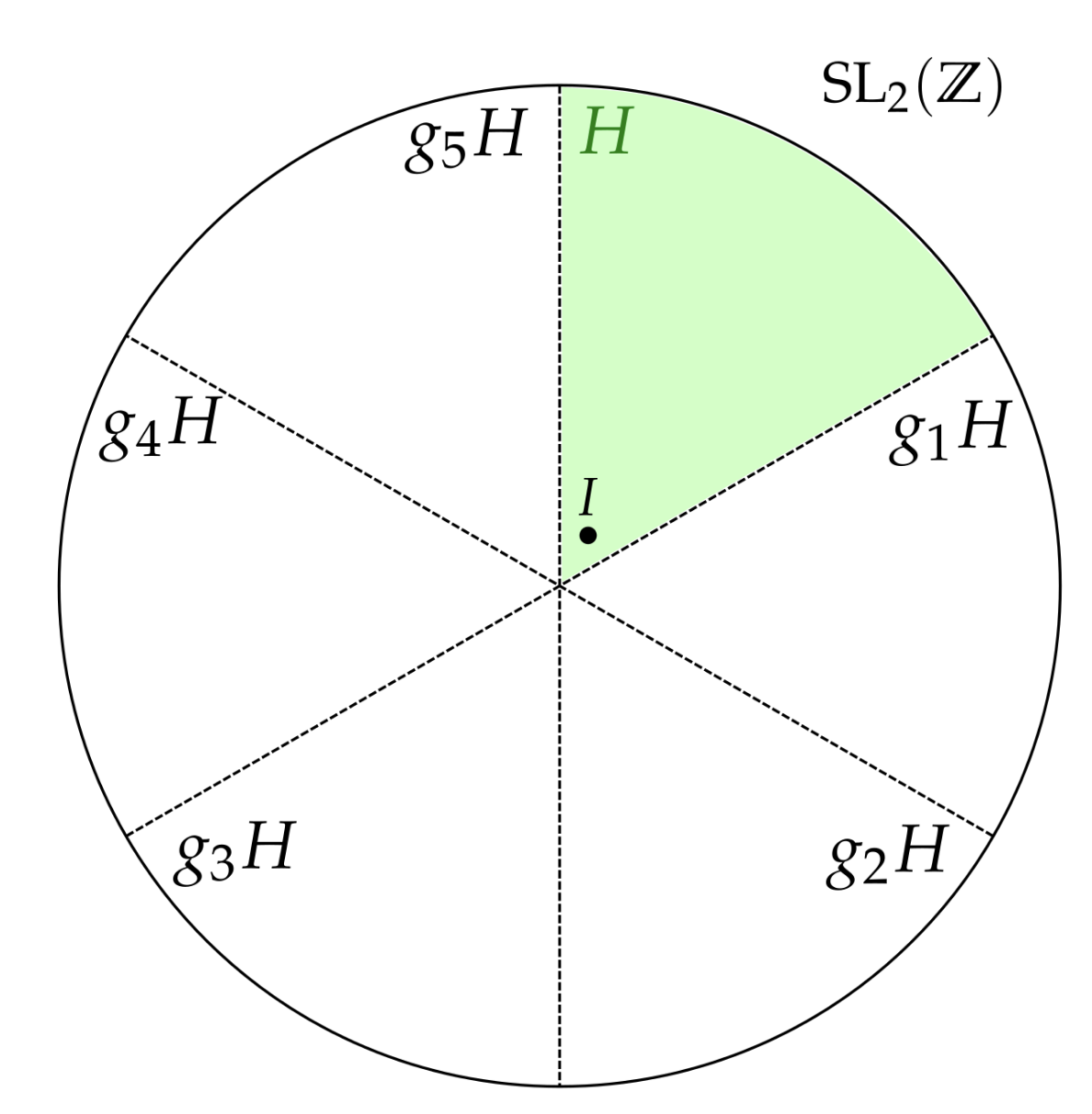

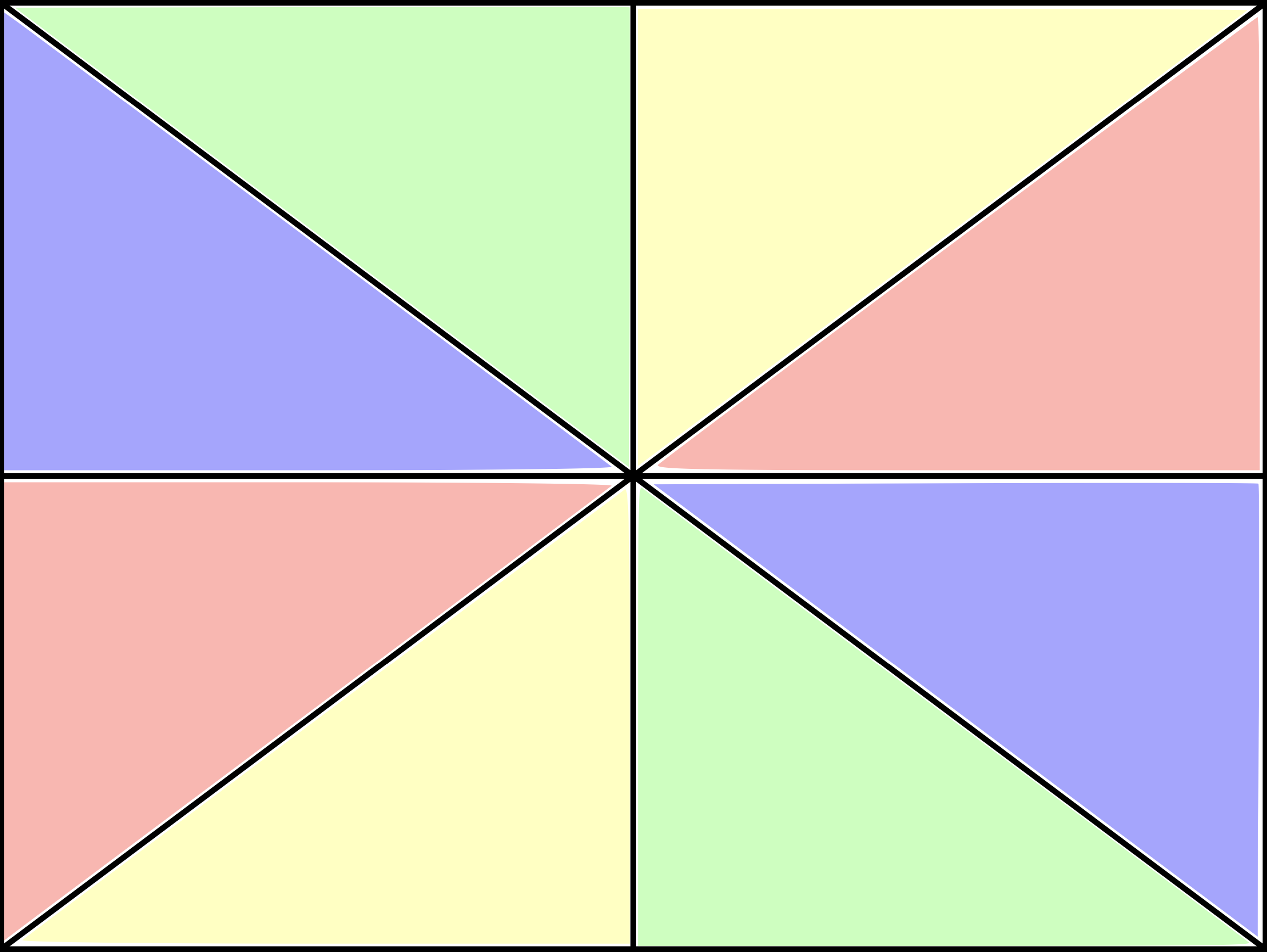

For here until the end $H\leq \mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ will be the Sanov subgroup defined before. A helpful visualization of copies of a subgroup sitting inside the bigger group is the following:

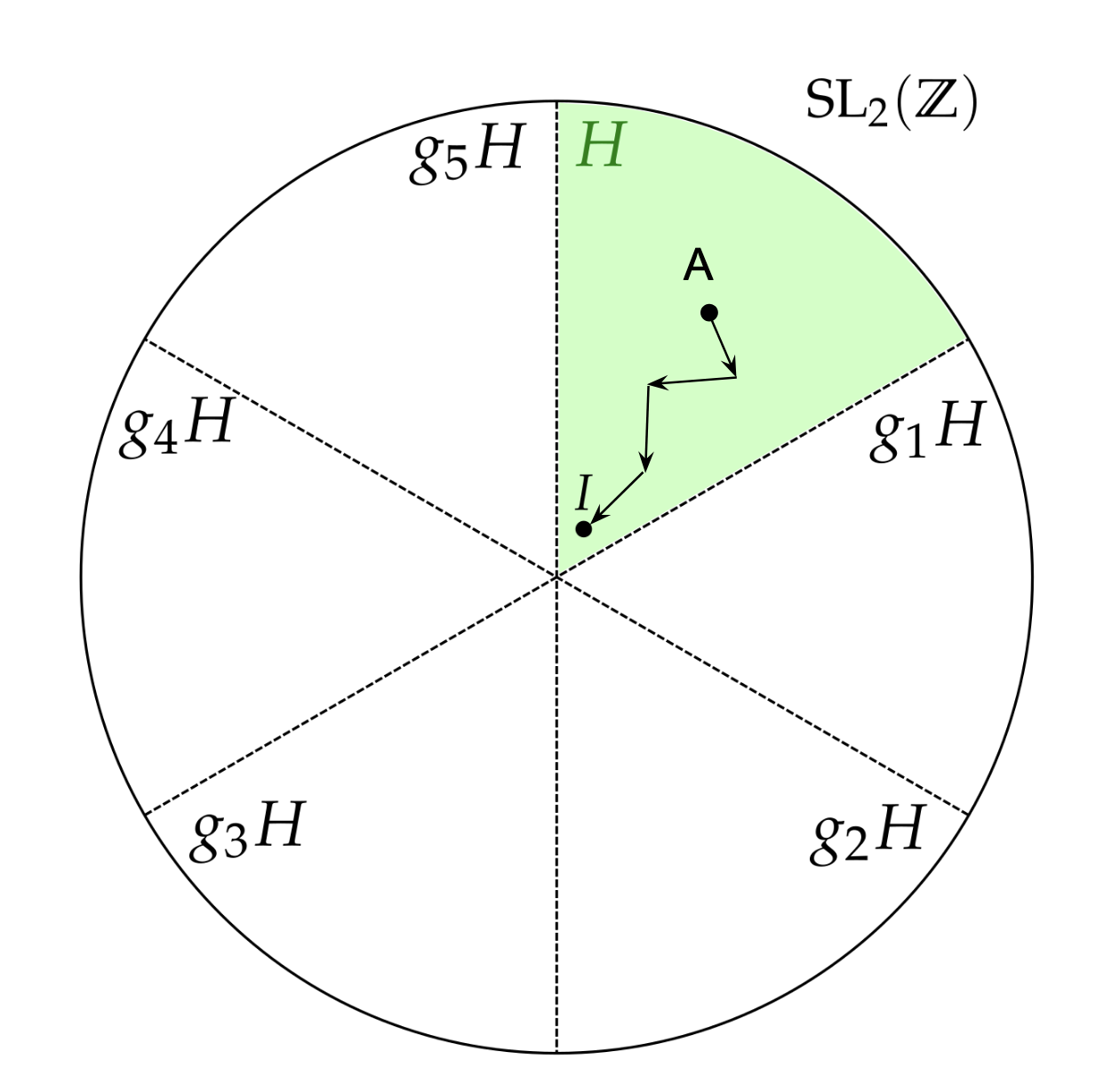

Here, there are finitely many copies of $H$ sitting inside $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$. I will now start calling these copies by their proper name in group theory, cosets, and we will denote them $H,g_1H,\dots,g_5H$. Let’s look at the coset $H$. Since each element of $H$ is a product of the matrices $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$, $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$, and their inverses (which we will call generators), we can imagine some path from any matrix, $A$, to the identity matrix $I=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$ created by multiplying these generators.

It is a fact from group theory that none of these paths cross into the other cosets (for example, a path in $H$ doesn’t cross into $g_1H$). Therefore, if we can find a path from any matrix to its respective “identity matrix” in any of the cosets, we can determine what coset it belongs to. We will call these “identity matrices” the coset representatives, as they represent the entire coset. An example of a coset representative that is useful to us is the matrix in the coset with the smallest valued entries.

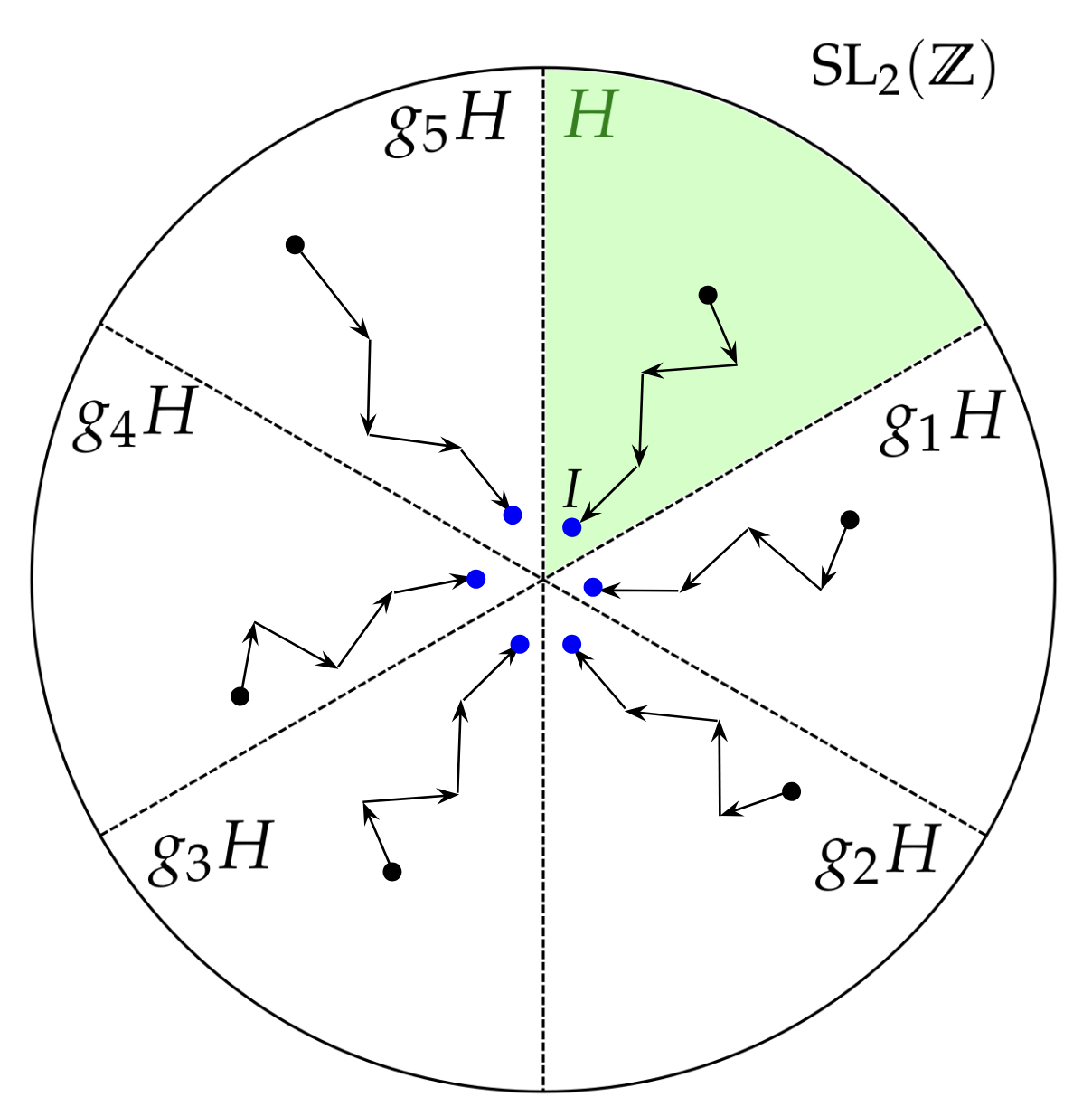

Therefore, if we choose random elements of $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$ and they all seem to converge to some finite set of coset representatives, we have strong evidence that there are finitely many cosets, and therefore that the subgroup $H$ has finite index in $\mathrm{SL}_2(\Z)$.

What we hope the algorithm should learn: finding a path back from any matrix to a coset representative (in blue).

Here, specifically, is what we want the machine to answer:

Given a matrix $A$, which generator should it be multiplied by to get closer to the coset representative?

Our hope (as mathematicians)

What we want out of the machine is not some algorithm that works for the matrices we feed into it. Strong numerical data is not proof. What we really want is an algorithm that we can prove shows the finite-ness of the subgroup index. With that in mind, here are our results.

What did the machine learn?

Our machine learning model took the first column of the matrix as input and would output one of the four generators that, when multiplied to the matrix, gets us closer to the identity.4 We trained a feedforward neural network with $3$ hidden layers (with $128$, $64$, and $16$ nodes), sigmoid and softmax activation functions on data on paths from matrices to the coset representative in the coset $H$. We used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of $0.003$ and the categorical_crossentropy loss function.5

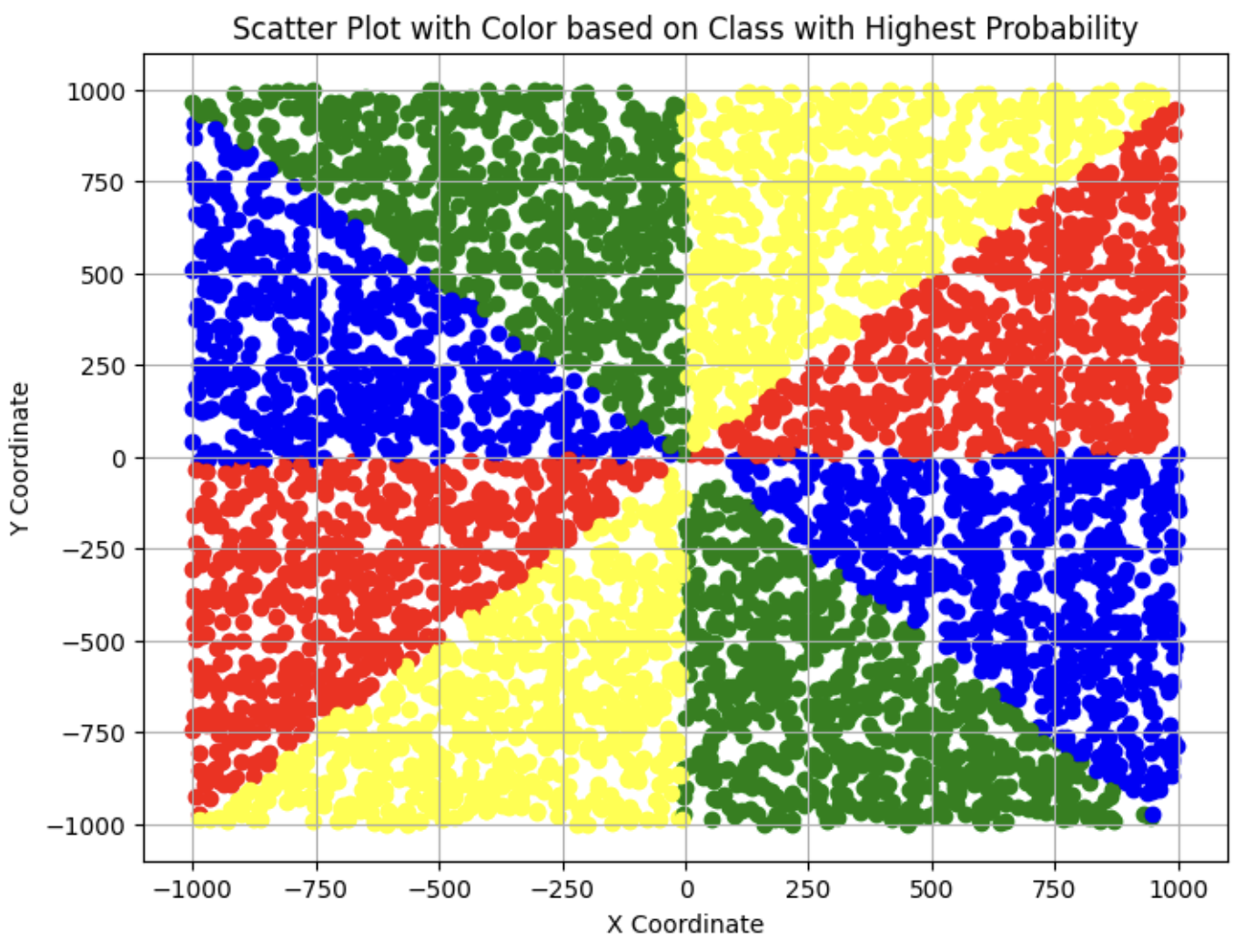

Here are the resulting decision boundaries our machine learned:

Each color corresponds to a generator. For example, when we use the matrix $\begin{bmatrix} 13 & -3 \\ -30 & 7 \end{bmatrix}$, the model sees the vector $\begin{bmatrix} 13 \\ -30 \end{bmatrix}$, and it applies $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$ to get

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 13 & -3 \\ -30 & 7 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 13 & -3 \\ -4 & 1 \end{bmatrix}. $$

Notice that this reduces the size of the entries in the matrix, as we expect the model to learn.

Extracting ideas from the model

One thing about these decision boundaries is that they are nearly linear. Since our activation functions were not linear, the model did not create exact linear decision boundaries. However, we as humans can infer that the model is trying to make the decision boundaries on the $x$, $y$-axes and the lines $y=x$ and $y=-x$.

So the machine seems to be learning this algorithm. What’s the significance of this? Well, it is exactly the textbook approach for proving that the Sanov subgroup has finite index!6 So, the machine approximately created a provably correct algorithm that shows the Sanov subgroup has finite index. So, to some effect, the machine was starting to learn how to prove something about a group!

A caveat

The model was doing a great job at nearly getting a linear decision boundary, which may make it seem like most matrices will get back to a coset representative like in the algorithm for the written proof.

However, in practice, we found that most matrices did not find their way back to the representative when using the machine learning algorithm; small inaccuracies in the model led to wrong decisions “blowing up” and preventing us from reaching the coset representatives (thanks Jordan for reminding me of this!).

Whether we can get around this obstacle is still a question to work on. Perhaps working with a model that creates linear decision boundaries would have panned out better for this specific subgroup, but we would have to see how it extends to other subgroups as well.

Potential for mathematics

I will admit that the last step - using human inference to get the decision boundaries - is at odds with to the dream of AI fully developing a mathematical proof. Moreover, the algorithm itself is obfuscated by the matrix multiplication and turns out to be quite simple: take the vector and use twice the smaller value to decrease the absolute value of the larger value. Given the right cost function, this would be easy for a machine to learn. However, learning this algorithm revealed to me that there is some potential of a machine understanding the algebraic structure of the modular group, which was far more than I expected coming into this research. Hopefully, we can apply this approach to subgroups with unknown index!

Overall, this project has opened my mind to using machine learning techniques to verify mathematical problems. The people at DeepMind have shown several examples of using AI models to make entirely new discoveries in math, using incredibly novel methods in artificial intelligence to do so. In contrast, I think our project prototyped how simple machine learning models could assist us in math research.

For an introduction to modular forms, I would recommend Keith Conrad’s notes, which were used for this lecture series. ↩︎

I glossed over the details because it did not concern our project. The precise definition is holomorphic functions $f \colon \mathbb{H} \to \mathbb{C}$ such that there exists a $k \in \Z$ so for all $z$,

$$ f \left( \frac{az+b}{cz+d}\right) = (cz+d)^k f(z), $$

and that $f(z)$ is finite as $z \to \infty$. ↩︎

https://www.ams.org/journals/notices/201906/rnoti-p905.pdf ↩︎

We did this to get a visualization that did not require $4$ dimensions. The condition that the determinant is $1$ actually means that this reduction doesn’t lose much data for most matrices. ↩︎

We also worked on more direct algorithms, such as breadth-first search, and other machine learning models, such as Q-learning and Monte Carlo Tree Search. However, we had the best results with standard neural networks. ↩︎

See Löh’s Geometric Group Theory: An Introduction (Proposition 4.4.2), for example. ↩︎